3:10 to Yuma (1957)

I want to riiiiiiiiiide agaiiiiin—on the 3:10 to Yuuuuuuuuuumaaaaaaaaaaaa…

Ah, Frankie Laine, I hear you singing this song in my head more often than I’d care to admit. But what can I say? It’s catchy and moody, and it reminds me of a great movie—a movie that reminds me that there was a time when films about murder and mayhem and evil deeds tended not toward one-dimensional characters and simple battles of good-versus-evil but toward complexity, gray areas of the soul, and open-ended questions.

Before we talk about today’s film, 3:10 to Yuma (1957), I’m going to take this opportunity to go on a short yet potent rant about the merits of restraint in cinema. Ready? Let’s dive in.

Sex and gore in modern cinema

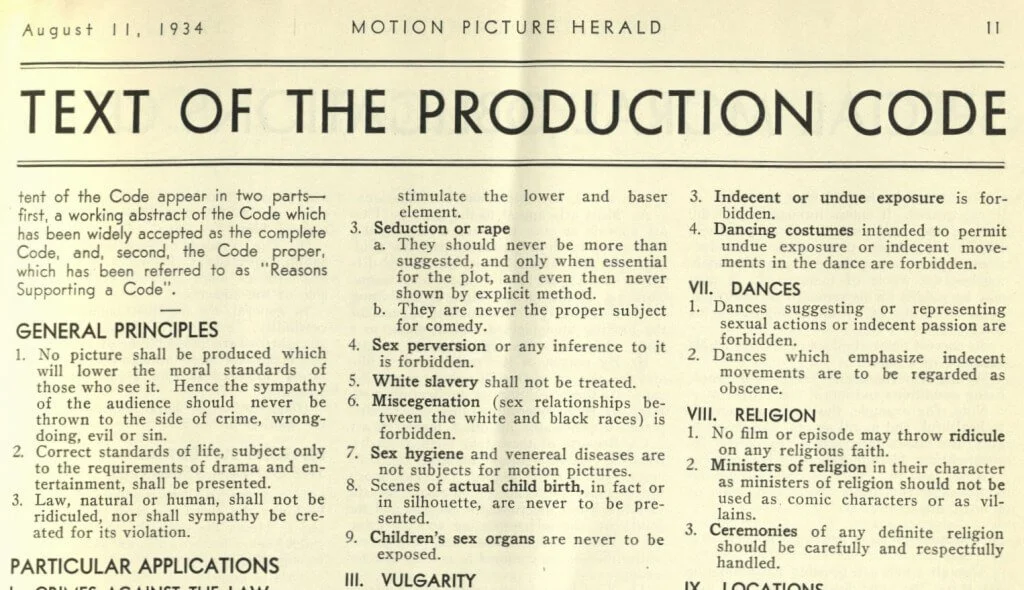

I’ve often heard the argument that the Hays Code and the general norms and mores of the mid-twentieth century made for less gritty and realistic films than modern Hollywood produces. While I do think the concept of a film “morality code” is, ahem, ridiculous, I don’t necessarily agree with this overall sentiment. IMHO, gore in modern cinema, as a general rule, is used as a shortcut: a way to tell audiences that someone is hurt without having to delve into complicated emotions and motives.

When you can’t rely on visual gore, however, you have to deal with those emotions and motives with nuance and subtlety, something that (and this is probably a hot take) is largely dulled in modern cinema. I won’t linger here too long as I’m contemplating a separate post about this topic, but suffice it to say that in a world where what matters is content rather than art, some restraint is, to me, quite welcome.

Alice Eve in her underwear in Star Trek Into Darkness (2013)…because the plot would have fallen apart without this shot?

Now don’t get it twisted: you’ll never hear me argue that movies should never swear or show gore or sex. I don’t think that. But when those elements are gratuitously relied on as a way to make a movie clippable, meme-able, shareable, viral-able—because that’s what matters now—it tends to come at the expense of expressive, complex, and developed characters and nuanced stories that live in the gray area between good and evil, right and wrong, likeable and unlikeable.

I hate to quote a greedy, evil, crusty tycoon, but C. Montgomery Burns from The Simpsons sums it up nicely: “Call me old-fashioned, but movies were sexier when the actors kept their clothes on! Vilma Banky could do more for me with one raised eyebrow…”

Mr. Burns from The Simpsons rhapsodizing about Vilma Banky, a silent film actress, in S03E05 “Homer Defined.”

When you cannot or do not show things like gore and nudity, you have to invest more in building emotional connections with characters and writing creative, engaging stories. This is what leads to art. Not content—art.

3:10 to Yuma (1957)

Dan Evans (Van Heflin) holds a gun to Ben Wade (Glenn Ford) in 3:10 to Yuma (1957).

Which brings us back to 3:10 to Yuma (1957). Highly clippable? No. Likely to go viral? No. Worth every second of runtime? Yes, emphatically, yes.

For those of you who don’t know, 3:10 to Yuma (1957) is a Western about Ben Wade (Glenn Ford), the leader of a band of robbers who hold up a stagecoach in the beginning of the film, culminating in the death of the driver at Wade’s hands. When Wade is captured later in a neighboring town, the marshal offers a cash incentive to any two men who will take Wade to nearby Contention City and onto a train (the 3:10 to Yuma, if you hadn’t guessed) that will transport him to a major town where he can be tried for his crimes.

Enter rancher Dan Evans (Van Heflin), whose farm and family are struggling due to an ongoing drought. Attracted by the large sum of money, which could help save his farm, he volunteers to be Wade’s escort. Wade and Evans make it to Contention City, where a hotel room is waiting for them to while away the hours until 3:10.

So they wait. And they wait. And then they wait some more.

From a hotel scene in 3:10 to Yuma (1957). Can’t you just feel the tension?!

This is my favorite part of the movie, where you’re just sitting in the discomfort, letting the tension build. Evans has a shotgun in hand, ready to fire out the window when Wade’s gang, who evaded capture, come to rescue him. Wade tries to bait Evans, mocking him for his struggles, teasing him about his family. He even tries to bribe Evans, promising him even more money if he releases Wade. Evans refuses. The tension builds some more. The clock is ticking on. The sweat is beginning to pool on their faces. The shadows get longer. And all the while, the 3:10 to Yuma comes ever closer.

I don’t want to spoil the ending if you haven’t seen it—and I highly recommend that you see it. I will tell you this, however: the choices that are made as the film approaches its end are complex and surprising, and as the 3:10 to Yuma leaves Contention City and it finally, finally, starts to rain, you don’t know whether to be happy for Dan Evans’ farm or horrified that he chose to put himself in this precarious position, endangering his life and his family, for money it turns out he didn’t even need.

Character and story in 3:10 to Yuma (1957)

Glenn Ford as Ben Wade in 3:10 to Yuma (1957). Look at his eyes—he’s not doing anything but lying on a bed in a hotel room, but you can see the calculation, the cunning, in this one glance.

This is not a movie about cowboys shooting each other up, although there are some cruel deaths in this film. Rather, it is a movie about the complexity of human nature, conscience, and the choices we make that define us. While none of the characters go through what I would call a dramatic arc, this movie makes you think. It is playful yet deep, and you don’t know whom to root for (the honest rancher who’s just doing good for the money? the thieving murderer with surprising humanity?).

And despite there being sex, multiple murders, and attempted murders in this film, the gore is not shown, and the visual violence and sexuality are kept to a minimum. There is something to be said for showing “more” in a film to connect with audiences, but I also think it’s interesting how films were able to convey these things successfully when they were not allowed to rely on buckets of blood, dead bodies, and naked women.

Because here’s the thing: if you’re making art, if you’re telling a compelling and engaging story with nuanced and relatable characters, if you’re tapping into shared humanity, you don’t need those things. They become optional add-ons rather than necessities, set dressing rather than the only way you can connect with audiences.

Closing thoughts on 3:10 to Yuma (1957)

A poster for 3:10 to Yuma (1957).

I feel like so many modern movies just pass through your brain without leaving a mark, and that’s not what a movie is supposed to do. This film, despite its notable lack of breasts and blood, leaves an impact. I first saw this film almost a year ago, and Frankie Laine is still in my head. The hotel scene is still in my head. The ending is still in my head. It left its mark.

As a closing thought, when I was doing research for this post, Google (who is always watching) naturally recommended search queries from other users that I may be interested in. The top recommendation? “Is 3:10 to Yuma (1957) worth watching today?” (As a side note, what kind of age are we living in that you have to ask Google if a movie you’re interested in is “worth watching”?)

Nevertheless, the answer to your question, anonymous Googler, is a resounding yes.

Camille