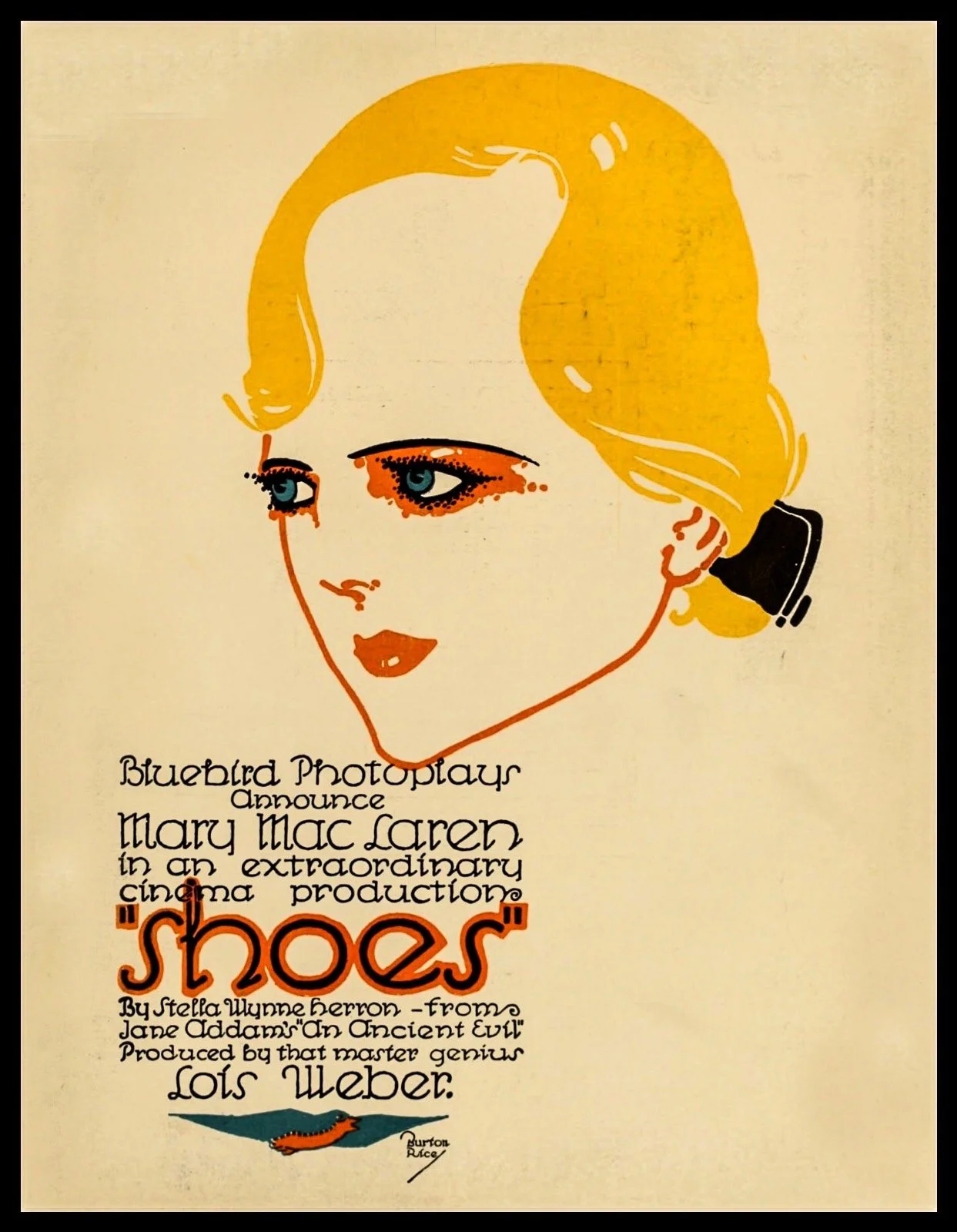

Shoes (1916)

What is Shoes (1916) about?

How far would you go to get what you need? How do you reconcile duty and independence? How much do you owe your family?

These are some of the questions explored by Shoes (1916), a silent film about a young woman who has to support herself, her parents, and her siblings on a paltry shopgirl’s salary, all while desperately needing and longing for a new pair of shoes.

That’s right, folks, we’re starting off by going hard: let’s talk Progressive Era poverty, neglectful parents, and people being driven to desperate acts to meet their basic needs. It’ll be fun!

But first, a little history.

The Progressive Era in the United States

The Progressive Era in the United States (lasting roughly from the 1890s to the 1920s and encompassing the time when this film was released) was marked by a LOT of change. Growing industrialization and the promise of a better life working in the country’s many new factories led to rapid urbanization. Come to the city, earn more money, improve your quality of life—that was the proposition that made some very rich…and some very, very poor.

A new middle class started to emerge, and stores, parks, and transit systems were built to accommodate these new city dwellers. But for others, overcrowding, poor sanitation, and a lack of accessible or useful services made life worse. The wealth gap continued to widen, and those on the wrong side of it rarely got to move up from the slums and underpaid jobs that were relegated to the lower classes.

(Didn’t I promise this would be fun?)

Eva Mayer’s dilemma

Amidst this rampant poverty and poor quality of life, enter Eva Mayer (Mary MacLaren), the protagonist of Lois Weber’s 1916 film Shoes. Eva works at a five-and-dime store and is the sole breadwinner for her three sisters and her parents (including her long-suffering mother, who struggles to hold the family together on Eva’s salary, and her lazy and neglectful father, who refuses to seek work in favor of lying in bed and reading all day). In addition to her family’s poverty and Eva’s feelings of responsibility for all five of them, Eva’s shoes are falling apart at the seams. She crafts new soles for her shoes out of cardboard, and she has to remove splinters and mud from her feet at the end of the day.

So when Eva’s friend offers to “introduce her” to wealthy local singer Charlie, Eva is faced with a dilemma: she can keep waiting, hoping her father will find work and continuing to believe her mother’s promises that next week, no, really, next week we can afford a new pair of shoes for you, all the while living in physical agony and frustration…or she can sacrifice her dignity, just this once but in a major way, and finally—FINALLY—afford her new shoes.

What would you do?

Well, spoiler alert, but one night Eva doesn’t come home until the early morning. She can finally afford her new shoes. As she is being consoled by her horrified (yet, for the time, surprisingly understanding) mother, her father makes an announcement. He has, at long last, found a job.

The End.

Whew.

Poverty, choice, and the enduring message of Shoes (1916)

Upon its release, Shoes was met with widespread critical and commercial acclaim, receiving praise for its realism and portrayals (all except for a few critics who were offended by the film’s gritty, raw depictions). It was so popular, in fact, that in 1932 a parody film titled The Unshod Maiden was released, adapting cuts of the original footage with voiceovers and turning it into a comedy.

Interesting choice.

This film hit me right in the gut, slowly and increasingly, then twisted a dagger into my heart at the end. Something I really like about this film is the ambiguity with which it ends. Many films from this time do a lot of moralizing: There are right and wrong ways to behave, right and wrong choices to make. Shoes eschews this in favor of ending on an open question. It shows quite clearly that Eva lives in a state of constant deprivation, desperation, and obligation, and she does not make her decision to meet Charlie lightly. She is wracked by feelings of sadness, guilt, and shame by what she has done, but at the same time, she now has her shoes.

This particular scenario may be hard for modern audiences to understand; we can walk into Target and buy a pair of knock-off Keds for fifteen dollars, and most of us already have multiple pairs of shoes at home. The concept of selling your body for a single pair of shoes might seem foreign.

But the desperation brought on by poverty has not changed. The landscape of the country and the ways in which poverty manifests and in which we can earn money have evolved into something unrecognizable from the Progressive Era, but poverty is still poverty. Desperation is still desperation. And the choices some of us must face between dignity, virtue, and ethics on one side and subsistence, survival, and success on the other are alive, well, and becoming more complex. The country’s Eva Mayers never disappeared—they just changed shape.

This should be required viewing for everyone.

P.S. I promise we’ll have more fun in the next one.

Camille